The BMW engineers were huddled together, with worried looks on their faces.

Was something wrong with their equipment? Was this a mechanical issue or a mistake in calculation? Whatever it was, it had not happened in any of their previous development tests.

Actually, the explanation was simple and straightforward, and we offered it eagerly.

But before we share the solution, we need to share what led up to the engineers’ predicament.

In the summer of 1996, BMW celebrated the 30th anniversary of its 3 Series. As part of that celebration, the German automaker took over the Grand Prix racing circuit at Jerez, Spain, and a nearby resort hotel. Invited in waves were automotive writers from around the world, with those unruly Americans being the last on the calendar.

Upon arrival, we spend the day driving across the Spanish rural countryside on wonderful tree-line roads in cars BMW has brought from its museum in Germany, cars that preceded what we know as the 3 Series, such as the delightful 1500 and spunky 1600, the later available as a coupe or sedan and introduced as part of BMW’s 50th anniversary celebration in 1966.

While BMW traced its 3 Series to the 1600, which offered not only a back seat and trunk but performance as well, it was the 2002, with its back seat and trunk and sports car performance that was the first sedan to lap the old Nurburgring circuit long course in less than 10 minutes and which established the pattern for such vehicles as the M3.

There also were the various generations of the 3 Series vehicles to drive, a visit to a winery that produces sherry (the English translation of the word jerez) , and other activities. But there also was one day with nothing planned between breakfast and dinner so one of the six Americans (me) asked if he might borrow a car and visit the Rock of Gibraltar, which was less than 90 minutes away via the A-381 freeway.

“I want to go,” said another at the breakfast table. “Me, too,” said another, and by the time everyone had a turn we needed two cars, which were granted, on the proviso that we also took along BMW’s American public relations person and had both cars back by dinner time.

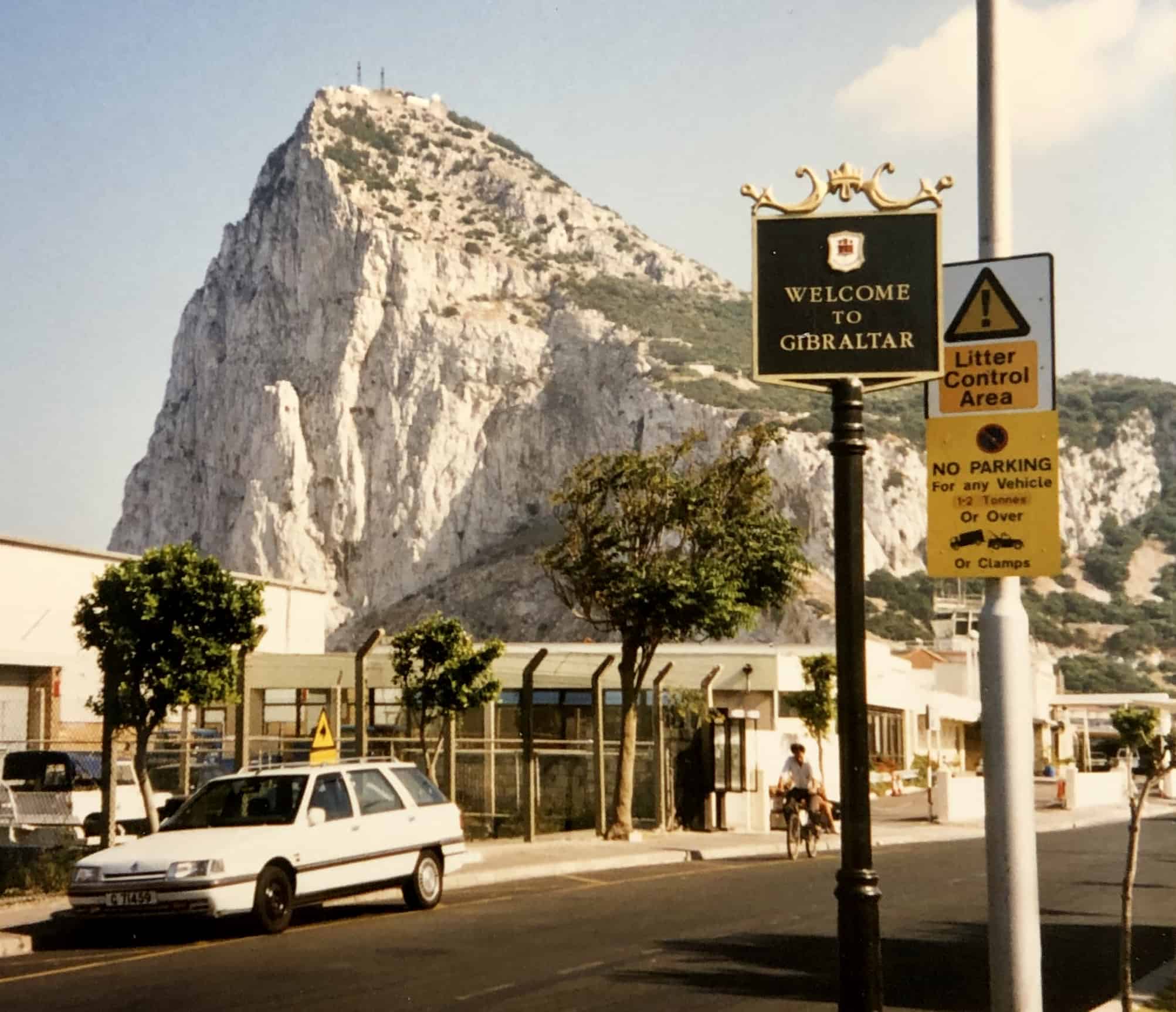

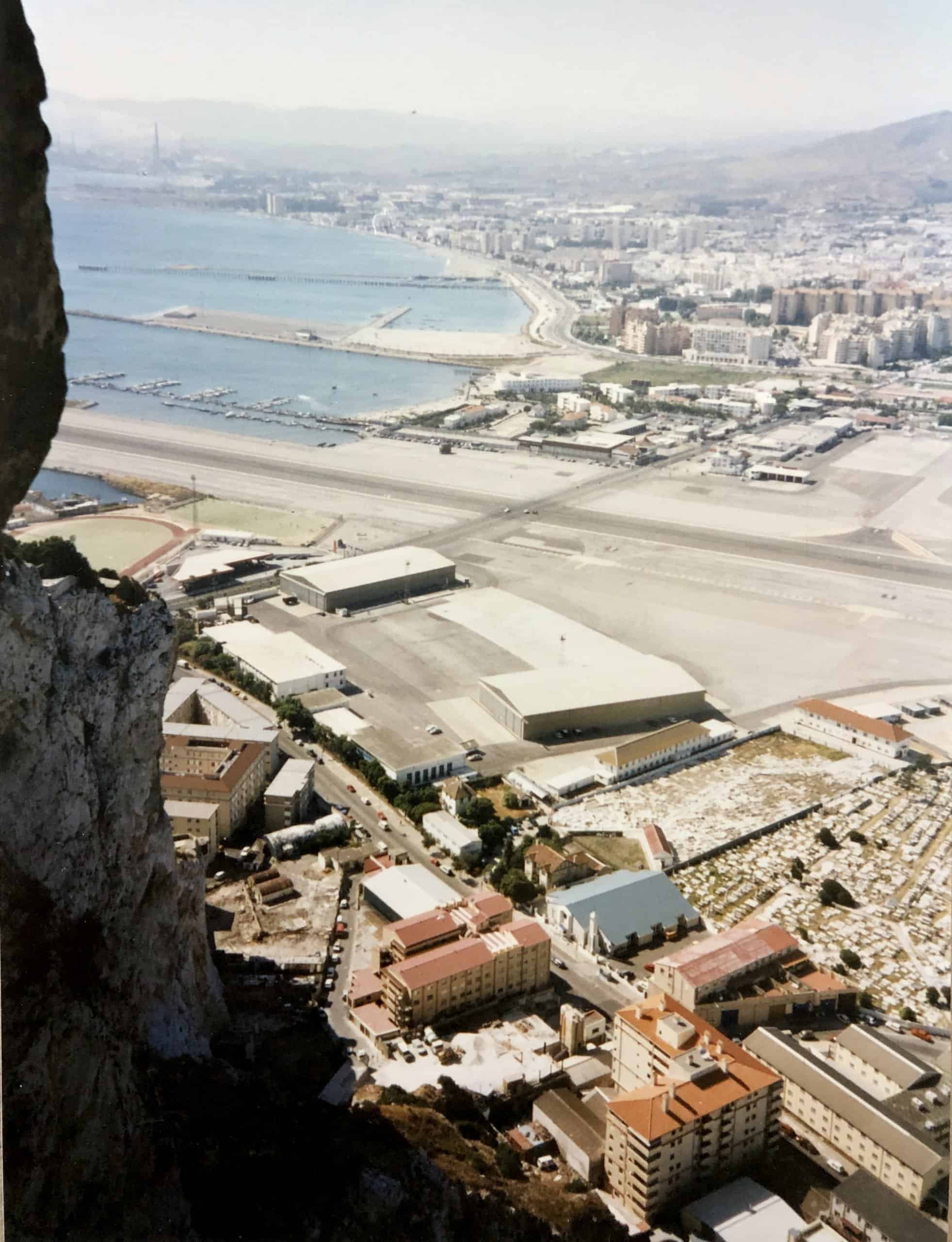

Arrival at Gibraltar was an unusual experience, since you not only are crossing an international border (Gibraltar is a British Overseas Territory) but the runway of the Gibraltar International Airport, Winston Churchill Avenue being the only road onto the peninsula and transgressing the runway to do so.

Once past the airport, we drove into what appeared to be a British village, parked the BMWs, and hired a guide with a van large enough for all of us for a tour that included going inside The Rock, which is full of holes like a big wedge of Swiss cheese.

Someone remembered our promise to return to Jerez by dinner time, we returned to our cars and headed back across the runway. Very quickly, however, our cars got separated and while one took the right route back, the other, the one I was in (no, I was not driving), took a wrong turn — OK, perhaps we decided to take a more scenic route back, and found ourselves on winding and scenic mountain roads, and at one point having to stop because one of those big Spanish fighting bulls was standing in the middle of the road and wasn’t eager to yield the right of way.

Our hosts were not happy as we arrived back at the hotel as the dinner tables were being cleaned. On the other hand, we had a great adventure story to share, and journalists are all about sharing stories.

Which brings us back to the story with which we started, and those engineers with worried looks on their faces.

As I recall, one of the last of our official anniversary exercises took place at the Jerez racing circuit, where the BMW engineers had turned one of the track’s straightaways into a drag strip so they could show off their new sequential transmission that was going into the M3.

Called the SMG — Sequential Manual Gearbox — the unit started with a Getrag 6-speed manual. There was a clutch, but no clutch pedal. Instead, with the gearbox in manual mode, a computer in the transmission and one in the engine communicated when the driver moved the shift lever to coordinate a perfect, rev-matching shift, up or down. There also was an automatic mode in which the transmission functioned like the typical automatic.

Oh, and unlike the Porsche Tiptronic or NSX’s automanual, the SMG had no buttons or levers connected to the steering wheel, because BMW engineers believed that drivers could become confused about which button or lever did what as they were turning the steering wheel.

To prove that the SMG made an average driver shift as well as a very good driver, the visiting journalists were invited to do back-to-back simulated drag runs in M3s with the standard manual and with the SMG.

The American “buff book” contingent included six of us, and after we’d done our runs, the BMW engineers huddled with those concerned looks on their faces. When they finally broke their huddle, they approached us and were apologizing for the problem.

Problem? Well, as it turned out, five of the six Americans had posted faster times shifting manually than with the SMG. Something must be wrong, the engineers said, because this had never happened before. Everyone else, it seemed, was faster with the SMG.

If you thought the engineers had worried looks on their faces as they studied their data, you should have seen the look when we started to laugh.

What was so funny, they asked? We offered our simple and straightforward explanation: We’re Americans, we said. We may not be as skilled at road racing as writers from some other countries, but we grew up sprinting from stoplight to stoplight. It’s part of our heritage, a rite of passage. It’s in our DNA, D as in drag racing.

Nothing is wrong with your equipment. We simply know how to go in a straight line and to shift very quickly at the same time.

Oh, and our youthful experiences didn’t take place in a 3 Series or one of its predecessors, but with 3 on the tree or, in some cases, 4 on the floor.