If remembered at all, motorsports fans recall Sunday, August 13 1972 as the date Emerson Fittipaldi won the Austrian Grand Prix, and in doing so, all but clinched his first Formula 1 World Drivers’ Championship. At the other end of the grid that day, a smaller kind of history was being made.

A tiny, underfunded team led by a stubborn owner/manager/designer with a race car built in a one-car garage made its first and last start in a championship Formula 1 Grand Prix.

The story of the Peter Connew Motor Racing Team began two years earlier, when 24-year-old Peter Connew, who then worked for Team Surtees as a design draftsman, decided he could become a Formula One constructor. It was an odd decision for a man who had little to no interest in motorsports and came by the position at Surtees almost by chance.

When he discussed his intentions with others to race in F1 he was told he was mad, which served only to make him more determined, according to Connew’s cousin and team member Barry Boor. Not surprising behavior from someone who, as a young lad, fought hard to overcome the ravages of childhood polio. Apparently the Connew family determination is a source of pride, as Peter’s son Christopher shared with warmth, “my Dad is a bit of a character – I get a lot of my personality from him really. We are both belligerent sods.”

What sparked the dream was his first sight of John Surtees’s year-old McLaren, purchased by the former World Champion to drive until his first F1 car could be completed. “At the end of the year, Surtees left BRM and began making the TS7 Grand Prix car. As a stop gap, he bought Bruce McLaren’s M7C which we had to modify with new fuel tanks to meet a change in the regulations. It was one of those bright clear February days when the car was wheeled out, freshly painted, for the first time. The car was in a gorgeous red and the sun caught it and I thought, ‘I must build something like that’,” Connew said.

Peter was also driven by a dedication to logic that overcame the types of fears that would stop the rest of us dead. When asked why he started out by building a Formula 1 car and not something simple like a Formula Ford, he responded that he knew how to build an F1 car from Surtees; he didn’t know anything about Formula Ford.

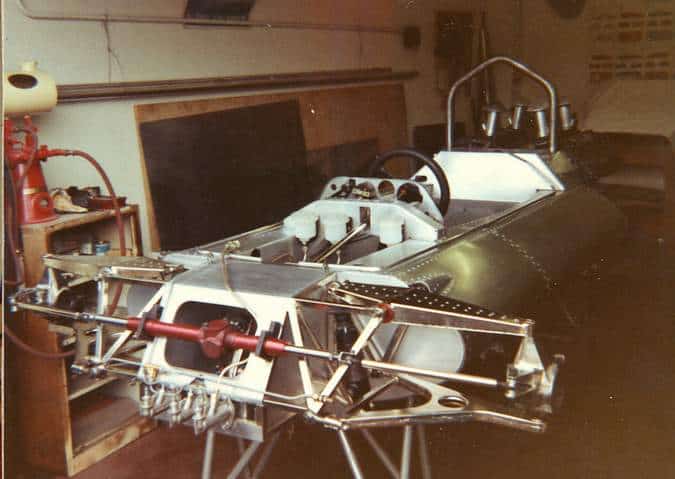

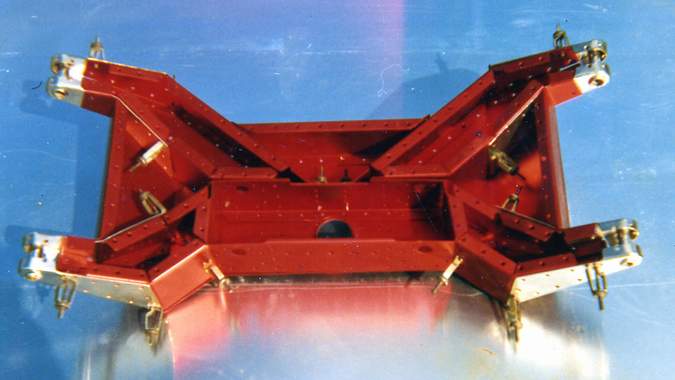

By December of 1970 a single-car garage had been rented in Chadwell Heath in northeast London and an aluminum tub began to emerge from the jig. The team’s miniscule budget went largely into raw materials, with friend and Chief Mechanic Roger Doran and his father machining, welding, and fabricating nearly every part of the chassis. Even the fiberglass body panels were created in-house by woodshop teacher Bloor. Keep in mind all this was accomplished in a space so small that one had to step over the race car in order to get from one side of the shop to the other.

The first of many obstacles appeared with a change in the regulations. The first tub was completed in 18-gauge aluminum to the existing standards. However, for 1972 the FIA required monocoques to be constructed of a 16-gauge aluminum. Work on a second tub commenced.

What couldn’t be made either in-house, or on equipment at a team member’s regular place of employment, was purchased at a discount or donated entirely from vendors with whom Peter had established a relationship while at Team Surtees. Avdel donated structural rivets while Girling provided brakes, Firestone tires and Armstrong dampers, all at no cost to the team. Gomm Metal Development, which fabricated tubs for smaller F1 teams, rolled the side panels and ‘forgot’ to bill Connew.

Given the team’s lack of experience and the limited resources with which they had to operate, one might assume a crudely finished final product, however, nothing could be further from the truth. Not only was the car professionally turned out, it also featured some cutting-edge design elements.

The radiator, located in the nose, was positioned nearly parallel to the road surface, with the intake air drawn from below. This provided for a flat, wide nose to generate downforce without resorting to larger, heavier and more complicated hip-mounted radiators. It also helped limit under-car turbulence. The rear suspension was designed with wide-based A-arms to eliminate the need for radius rods, which Peter thought unnecessary. Robin Herd used a similar design in the March 721X and radius rod-less rear suspension, soon after, became the de facto standard for Formula 1 cars.

When the chassis was completed, a borrowed mock-up engine and transmission were installed for a photo session at the local library’s car park. Peter brought those images, along with a scale-model of the car handmade by team member and first cousin Barry Boor, to sponsor presentations.

One such meeting was with Yardley, who unbeknownst to Peter had already signed with McLaren after ending their relationship with BRM. However, the toiletries giant was so suitably impressed with the young team they requested McLaren assist Connew in whatever ways they could. The first, and perhaps most important, benefit of this relationship was a fresh Ford-Cosworth DFV provided to Connew at a heavy discount (which Peter drove home in the front seat of his car). The team was in business.

Now only a driver was needed. Several of the day’s top young talent stopped by to chat with Connew, including Howden Ganley and Gerry Birrell. However, none could bring much-needed cash to the team. Instead a deal was struck for French F3 driver François Migault to drive in five European Grands Prix for a reported £40,000. Migault’s backers were a diverse lot, whose contributions were usually made in bundles of Francs, which, according to Bloor, team members then had to rush around London to exchange at different banks, as the maximum then allowed each day was only £30 per person.

While the team initially had Monaco targeted for their debut, it took until early July for the car to be ready to compete. The French Grand Prix, held for the last time on the Charade Circuit, was now chosen for the team’s debut. The crew loaded the PC-1 and their meager spares into a truck borrowed by Migault and headed south to Clermont-Ferrand.

Midway through France, the borrowed Ford D300 transporter blew its engine and was towed to the city of Le Mans for repairs. Migault, being a fils du Mans, suggested testing on the Bugatti Circuit before they head to Clermont-Ferrand, track rental apparently costing him little to nothing. Upon unloading the car, it was discovered that a rear A-arm had been damaged in transit and the team had no spare. The decision was made to skip the F1 race and instead stay in Le Mans, fabricate new A-arms and conduct some testing.

Little did the team know but the damaged A-arm wasn’t the result of improper strapping of the car in the transporter, as they then thought, but rather inadequately hardened coil over springs that yielded under load – a failure that would soon trouble the team again.

Team Connew’s next attempt to qualify would be at the British Grand Prix. In the first practice session, Migault put in an excellent performance but then the coil over springs yielded again. With the resultant suspension damage, Migault pulled off at the bottom of Paddock Hill. Despite his truncated session Migault managed a 1:30.2, just one second off the next slowest time from the same practice — which was a car that would make the starting grid.

The team grabbed the car and sprinted back to their shop to repair the damage, working for 40 hours without a break. Just as the police escort (that the team’s accountant had somehow arranged for) arrived to accompany the crew back to the circuit, a crack was spotted in a rear upright and the Connew team’s British GP was over before it had begun.

Despite two non-starts in a row, the Connew team remained optimistic as they headed to the Nürburgring for the German Grand Prix. It should be noted that at that time the National Sporting Authorities (ASN) had much more control of its own GP than it does today. So, when the Connew team arrived at Brands Hatch, they were welcomed as local lads and registered without issue. Not so with the ASN. As Connew had not submitted the proper paperwork before the race, the team was denied entry. And even though a petition was circulated and signed by almost every team requesting that Connew be allowed to compete, the German authority’s response remained the same: “Nein.”

So instead the team drove back to Le Mans for more testing, and two weeks later arrived at the Österreichring for the 1972 Austrian Grand Prix. Although the PC-1 had yet to qualify for a race, the team began to feel a part of the Grand Prix circus. New bushings were turned on McLaren’s mobile lathe and a Brabham mechanic helped cure a misfire caused by mis-routed fuel lines.

That year, the organizers had decided that 25 cars were to start the race, though 26 had been entered. The Connew team members were gravely concerned about their prospects. Driver Migault was held to a lower rev limit, which helped to preserve the team’s one engine, but cost speed down the track’s long front straight. He had qualified in 26th position.

Then luck smiled upon them; Frank Williams withdrew his March as driver Henri Pescarolo had damaged the car beyond repair in a practice crash. The Connew PC-1 would finally start its first World Championship Formula One race. “The fact that we were at the very back of the grid didn’t worry me, it was the fact we were on the grid, and it was fantastic” Connew said.

As the race progressed, “Frankie” (as the team had affectionately nicknamed their driver) had picked up several places. By the 21st lap, Migault was up to 17th, but on the 22nd lap, again disaster struck. An aluminum bracket that secured a lower rear wishbone snapped. Migault held it together to keep the car off the barriers, but the Connew team’s race was over, and with it, its Formula 1 Grand Prix career.

Team member Barry Boor figures that if the car had stayed together Migault might have finished as high as 11th or 12th, which would have provided enough prize money to continue on to the Italian Grand Prix.

So now instead of heading to Monza, Connew entered the PC-1 in a Formula Libre race at Brands Hatch. During the event, a circlip retaining a wrist pin had broken and allowed the corresponding piston to move about and eventually crack the cylinder liner. The team blamed their inexperience for the magnitude of the damage as other teams along pit lane had mentioned to them earlier that the engine sounded “off”.

That race marked the end of the relationship with Migault, of whom the team had grown quite fond (due, no doubt, to his sense of humor, enthusiasm, and willingness to work alongside the crew). It did end on entirely on good terms, though. Migault had been promised five F1 races and received one. Connew had been promised £40,000 but received only about a quarter of that amount.

The Connew PC-1 competed in one last non-championship Grand Prix, the end-of-season Victory Race at Brand Hatch. The driver was David Purley, whose father sponsored the effort through his Lec Refrigeration company, including a rebuild of the damaged Ford Cosworth DFV. “(Purley) asked for an engine kill switch to be fitted to the steering wheel but when its electrical wiring failed on the warm-up lap he had to retire the car,” said Connew. Once again, the Connew PC-1 was a non-starter.

There were a few undistinguished outings for the Connew PC-1 in 1973, converted now to Formula 5000 specifications, fitted with a Morand-built 5.0-liter Chevrolet V-8 and a more conventional rear suspension.

The final race for the PC-1 was another Formula 5000 round, this time with high hopes, as the driver would be former British F3 Champion and Monaco F3 race winner Tony Trimmer. During the race a shock tower broke which sent the car into the barriers. While Trimmer was unhurt, the PC-1 was severely damaged. Not surprisingly, given the role the circuit had played in the Connew story, the end came at Brands Hatch.

So, what became of the Connew PC-1? While the Ford-Cosworth DFV engine went to Tom Wheatcroft and the Hewland DG 300 transaxle went to Alain de Cadenet, surprisingly most of the rest of the car remained in Peter’s possession, albeit in pieces.

The two tubs sat in Peter Connew’s backyard for decades, however in 2016 the original team of Connew, Boor and chief mechanic and friend Roger Doran set about restoring of the car. With no engine or transaxle in their spares, they borrowed a blown DFV from motorsports historian Doug Nye and a Hewland gearbox from restorers Hall & Hall. The car made its non-running debut at the 2017 Goodwood Festival of Speed and was shown again the Motor Sports magazine Hall of Fame Live at the Race Retro event in 2018. Plans are to have a running example at some future Goodwood Festival of Speed, where no doubt it will be warmly welcomed.

The last word goes to Peter Connew: “In motor racing terms it was not a success. But in my terms, it was 100% successful. I set out to build a Grand Prix car and I built a Grand Prix car.”

As a former Life Racing Engines engineer, I sympathize with this valiant albeit unsuccessful effort!