Although I’ve been in my new house in a new state for about a month, I’m still unpacking boxes (a process I hope to complete by Thanksgiving, and if I accomplish that goal I’ll be very thankful indeed).

As much of a pain as moving is, the opening of each box — packed months ago for storage during the house hunt — has provided something of a treasure-hunt experience.

This past week I found another treasure, five letters I received in the 1980s from Charlie Moneypenny.

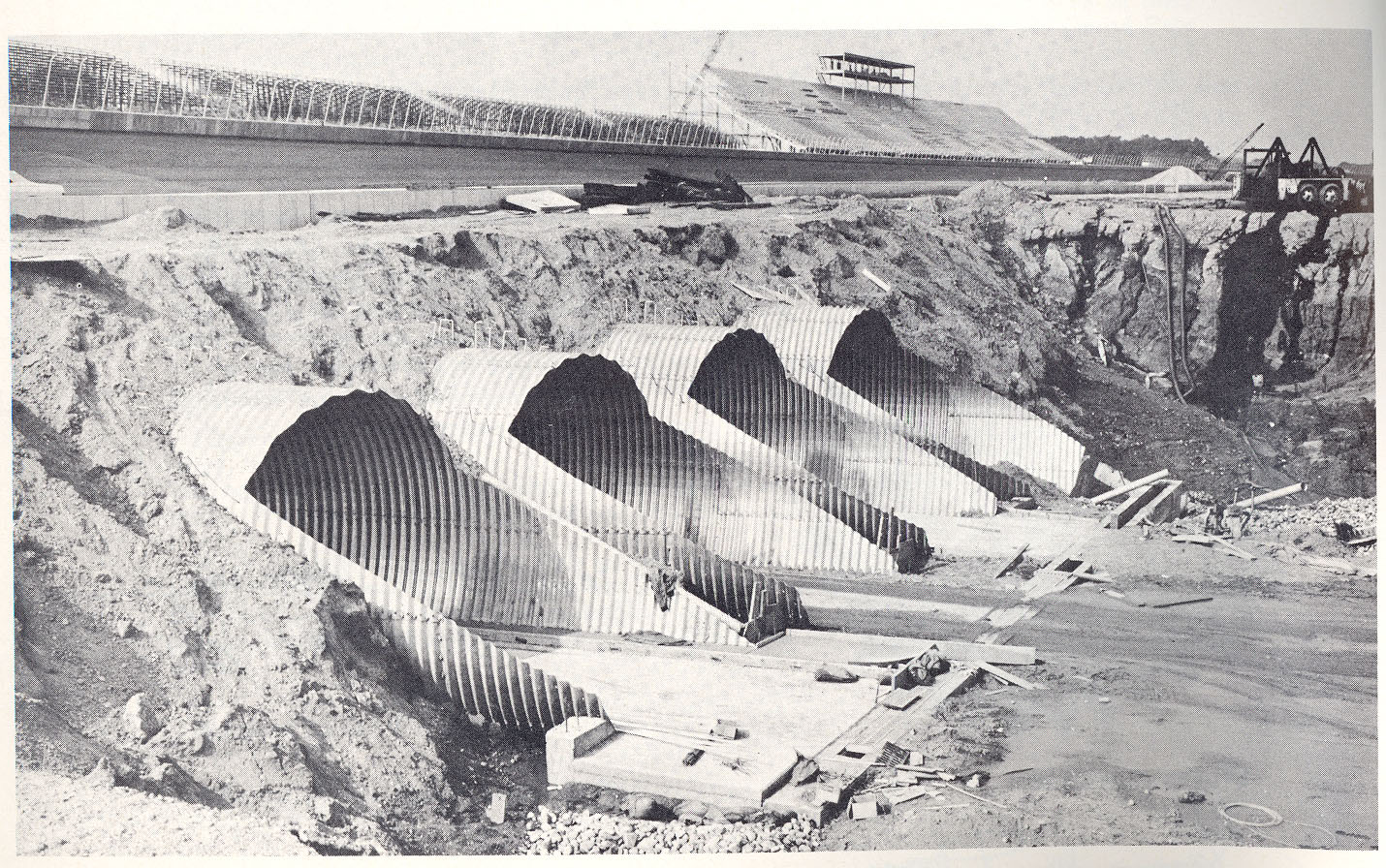

This Moneypenny was not the figment of Ian Fleming’s imagination, the secretary making moon eyes over Bond, James Bond. He was the engineer who designed, among others, the high-banked oval racing tracks in Daytona Beach, Florida; Cambridge Junction, Michigan; and Talladega, Alabama. He also did tracks in Texas and Japan, and consulted on several others.

In July, The New York Times published a story headlined “The Forgotten Figure Behind Daytona International Speedway.” The article noted that despite his contribution to the sport’s success, “Moneypenny is barely mentioned in the history of the sport. NASCAR archivists do not have much material on him. Ed Hinton wrote a book on the Daytona racetrack in 2001 and can barely recall Moneypenny’s name (except as James Bond’s assistant in the movies).”

I hadn’t forgotten Charlie Moneypenny nor his contribution to racing, and not just to NASCAR, but to Indycar and even sports car racing. I also remembered a couple of telephone conversations we had and his explanation of how the concepts for the banking for the race tracks was based on geometric formulas devised for the construction of banked curves for railroads.

Once upon a time, I was sports editor of a newspaper just up the road from Michigan International Speedway, and in 1983 I did a story about Moneypenny, at the time an 87-year-old retiree living near San Diego. Charles H. Moneypenny died in 1992 at age 96.

“After World War II, the Navy gave the city (of Daytona Beach) 500 acres of land,” I wrote. “When Bill France no longer could obtain insurance for the beach races, ‘I was in a position to suggest that (land from the Navy) might be a good place to build a speedway’,” Moneypenny told me.

Moneypenny was the Daytona Beach city engineer. France turned to him for help in building his new superspeedway.

To prepare for designing the Daytona track, Moneypenny returned to his native Michigan. He’d grown up on a small farm near Lake Michigan and later to a small town near the state’s capitol. He fought in France during World War I. After the war, he attended the U.S. Army Engineering Schools and did a detailed map encompassing a 20-mile radius around Norfolk, Virginia.

He engineered an oil pipeline in Mexico and supervised the layout and construction of a railroad in Honduras before engineering highways in the Carolinas and in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He took the city engineer job in Daytona Beach, he said, because of the warm year-around weather.

Back in Michigan in behalf of Bill France, Moneypenny worked for two months with mathematicians and proving grounds technicians at General Motors, equipping cars with measuring devices and driving them around the company’s banked test track at various speeds.

“We worked out formulas for the vertical and horizontal spirals in and out of the curves,” said Moneypenny, who copyrighted those spiral formulas and used them to give his tracks’ banking profiles that enhanced competitive racing and helped making NASCAR — and other series — so popular in the second half of the 20th Century.

Racer Neil Bonnett was among many drivers praising Moneypenny’s track designs, noting that they could safely race “three or four abreast… get five abreast coming down that front straightaway (at the Michigan track Moneypenny designed in the late 1960s).”