Part 1

“You have to understand,” a veteran Porsche engineer finally said to me. “Throughout our careers, we have been taught that if a journalist is present, we are to dig a hole and bury the car. And here you are, riding along with us.”

Two things you need to know: First, I had been riding along for most of two days before any of the engineers had spoken more than a polite guten Morgen. Secondly, this ride was taking place in super-secret Porsche prototype vehicles nearly two years before such vehicles would go into production.

Oh, and perhaps a third thing: We were riding through the Yukon wilderness in northwestern Canada, and it was only 30-something degrees below zero, and the engineers were disappointed. Their goal for such development test driving is to expose prototype vehicles to temperatures from 40 above to 40 below Celsius. In other words, a temperature range in Fahrenheit of 104 degrees above to 40 below (turns out 40 below is the same freaking cold figure on both temperature scales).

To document the development of its first sport utility vehicle, the Cayenne, Porsche planned to publish a book tracing the vehicle’s history, from first design sketch to first one rolling off the assembly line. Probably for considerations of marketing, the company wanted the book co-written by a German and an American author, I had been contracted as the American author.

Early on, someone in Stuttgart decided the home office needed more control over the process, so the American co-author was cut out of the book project. However, considering I’d already signed a non-disclosure agreement that had a $250,000 penalty clause if I divulged any details about the car before its unveiling, I was invited to join the engineers on two more of their development drives. While no longer co-authoring the official book, I could sell exclusive stories to car magazines once the embargo on such reporting had expired.

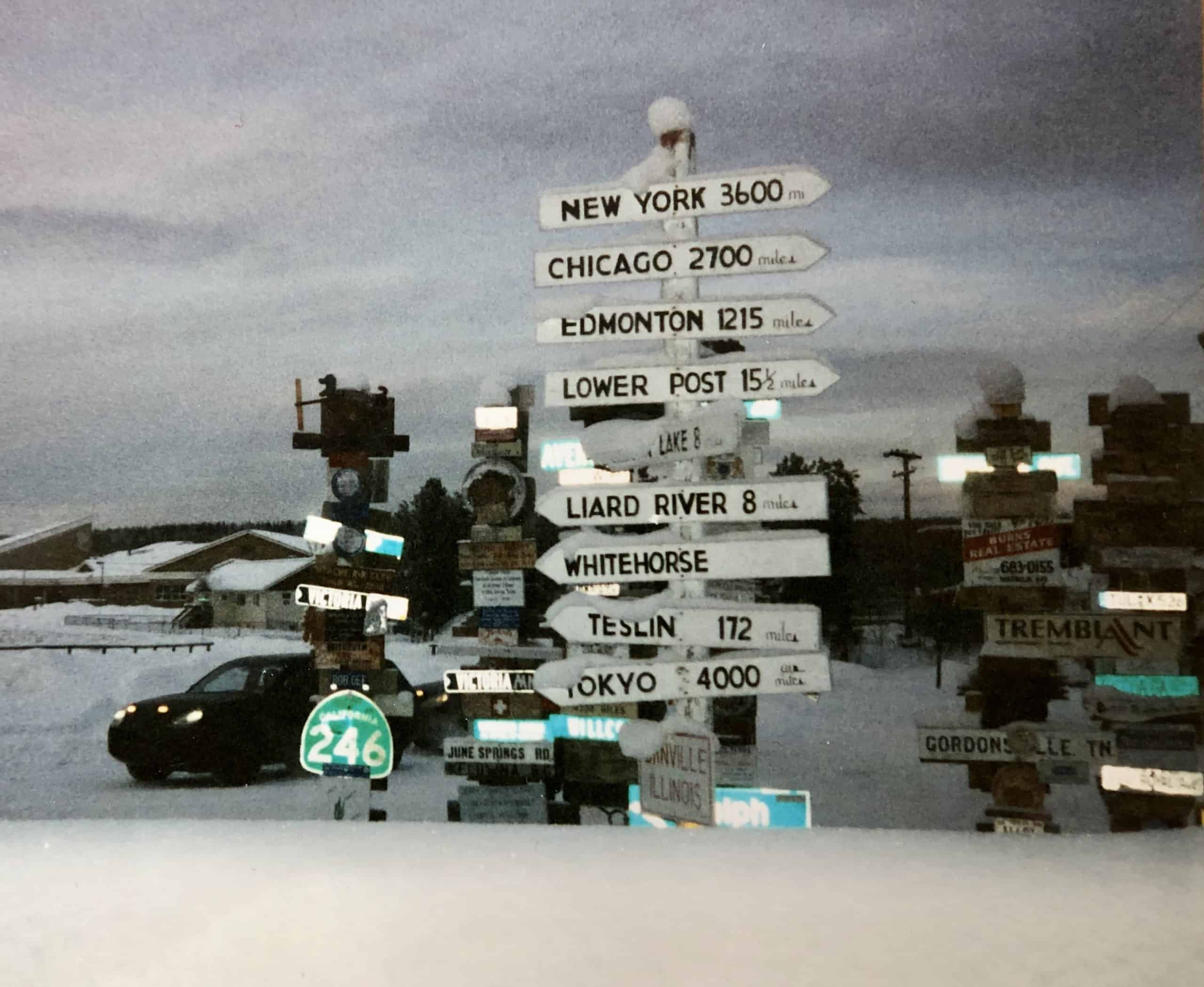

Just getting to Whitehorse in Canada’s Yukon Territory is an adventure of its own. First, we have to make our way to Vancouver, British Columbia, where we board a chartered 19-passenger Beechcraft and fly north, so far north that we have to stop on Moresby Island to refuel.

Our destination, as Canadians express it, is “north of the 60,” as in the 60th parallel of latitude, which marks the northern borders of British Columbia, Albert, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. To put it another way, we are more than 200 miles north of Juneau, Alaska.

Unfortunately, sports cars are sold in enough volume to keep Porsche in business, so the company decided to go along to get along and was in development of its first sport utility vehicle, internally code-named the E1. We — the engineers from Germany, Porsche’s North American head of public relations Bob Carlson, and me — are about to travel 5,000 miles by road, in several E1 prototype vehicles, to Calgary, Alberta.

At that point, some of the cars will be driven back north, this time to Yellowknife, in Canada’s Northwest Territory, for yet more winter testing.

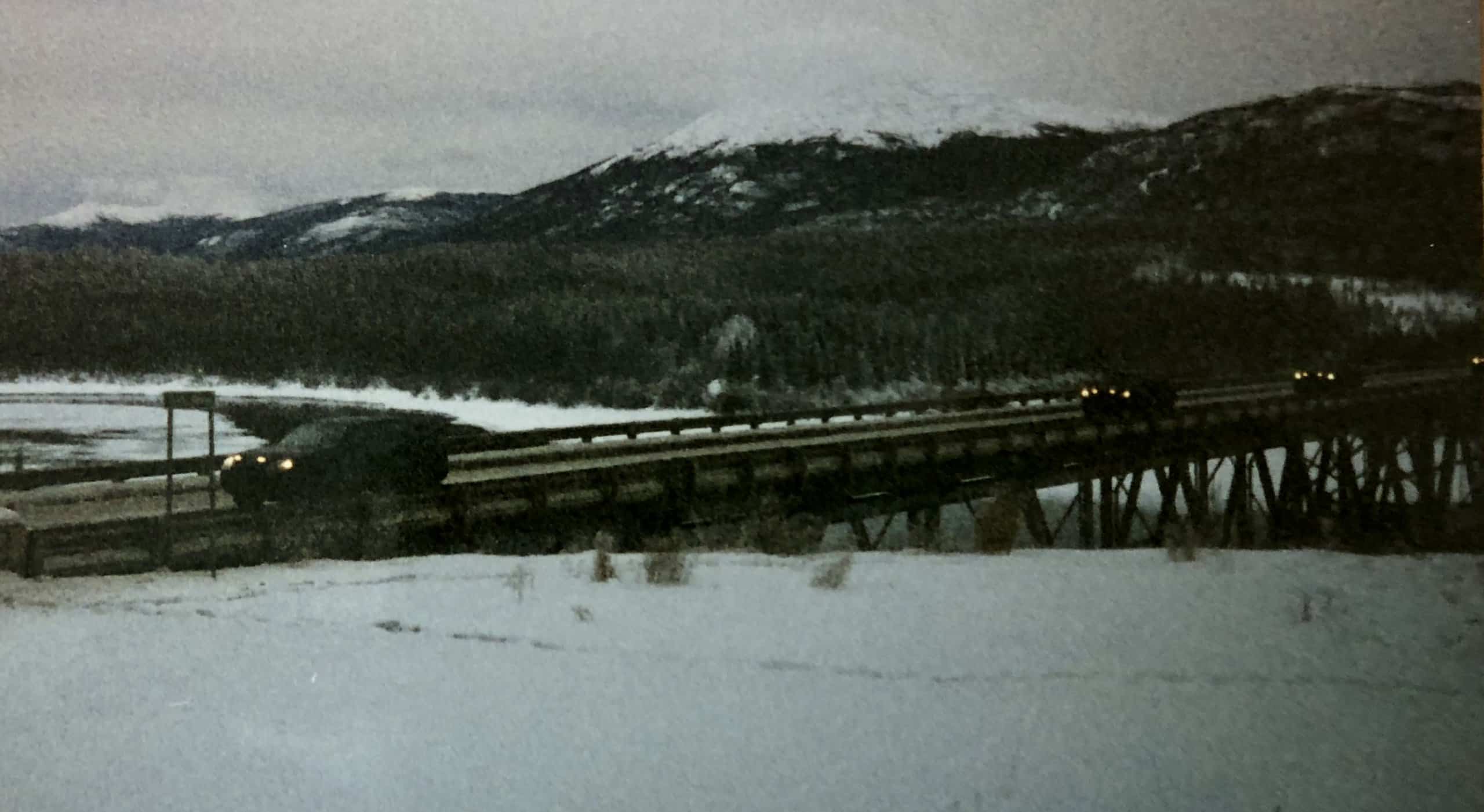

Much of our drive is done in darkness, or at least nearly so. We are so far north and in late January when the sun doesn’t break the horizon until 10 a.m. and then disappears back below it by mid-afternoon.

Forget that non-disclosure agreement, the cars are so thoroughly and heavily camouflaged that I couldn’t share secrets of the design even if I wanted to, though well into the trip, and after the engineers are convinced it is OK to have a conversation with the American journalist, I catch Peter Hass smiling as he looks at one of the prototypes from behind. Turns out he is missing his anniversary, as he does every year because of winter testing, and he’s admiring how the curve of the car’s rear quarter panel reminds him of the curve of his wife’s hips.

For my part, I quickly come to admire the engineers’ skills not only at their professions but as drivers. I’ve ridden shotgun with professional rally drivers and with experienced ice racers, but the Porsche engineers have amazing skill at driving at high speeds on narrow and ice-covered roads through the Canadian forests.

As the trip continues, I learn a lot about what it takes to develop a new vehicle from sketch to production and at the engineering expertise involved. Each engineer seems to have a specialty — brakes, powertrain, suspension, HVAC, even noise suppression — and has honed his knowledge through years of experience.

They are specialists, perhaps the best in the world at their respective disciplines. Before their work on the Cayenne, these engineers played similar roles in 911 and Boxster programs. And it’s not just the engineers but the development leadership as well. Before heading Cayenne development, Egon Verse was project manager for the Boxster.

The engineers’ work continues even after the driving is done each day. There is a daily debrief, and conference calls with counterparts back in Germany, and parts and components to be checked. One day, after a lot of snow, intake manifolds are inspected to verify they function as designed.

In addition to the Cayenne prototypes and a trio of other automaker’ SUVs — including the “Weissach Jeep,” a Grand Cherokee that for has been driving around Germany for some time carrying a variety of potential Cayenne powertrains for evaluation. There are two other vehicles along just to carry spares and alternative parts that need to be tested, plus two rented minivans for video and photographer crew and crew.

And while we’re in Canada, another group of engineers is in northern Sweden, testing new software for the Cayenne engines and stability control systems. The plan is for that powertrain software group to meet us in Calgary and to install the new codes for testing on the drive up to Yellowknife.

Another thing I learn: A moose and an elk are the same animal. At one point we pass a place where there is a very large elk standing near the road. “Moose!” the engineers warn each other on the 2-way radios.

“No, elk!” I say.

“No, moose!” the engineers in the car with me respond.

“No, elk!” I insist.

It is about this point that we realize we’re talking about the same creature, it’s just that what we call an elk in North American is what they call a moose in Europe.

Yet one other thing I learn, and very early on: If you brought a camera, you must keep it in your luggage at all times. Porsche has a video crew and a still photographer along to capture some images for the book, but one way to prevent leaks is to prevent photos.

But wait, what about the photos we see with this article?

Well, even in an era before cellphones, the engineers had cameras they used to take souvenir photos as they traveled, and by now the statute of non-disclosure limitations on the dark images I was able to capture on film with my point-and-shoot device, which I unfortunately had left in my luggage the evening the Aurora Borealis had put on such a spectacular light show up at the Arctic Circle.

In a few months, I’d be reunited with the Porsche crew, but this time it would be in the Southern Hemisphere, for a hot-weather test drive in the Australian Outback. But that’s another story, a story for Part 2.