Article written by guest writer Doug Campbell, Superformance

Twelve years ago, I was thumbing through my fresh March 2005 issue of Road & Track. I typically skim the magazine, then go back later and read the articles that piqued my interest. I ground to a stop on Tom Cotter’s article about the new Superformance Daytona “Brock” Coupe. Until then, I knew very little about Carroll Shelby, Phil Remington, Ken Miles, Peter Brock, or any of the rest of the Shelby American team. The Daytona Coupe was the most beautiful automotive shape I had ever seen, and I became obsessed with learning as much as I could about the original Daytonas as well as this new version from Superformance. Two weeks later, I ordered a Daytona, which now has over 50,000 miles and many hours of track time.

Two things struck me about this car. First was the whole story of the original car: how a team of hot-rodders from Southern California went to Europe on a mission and kicked Ferrari’s ass in their own backyard. The Daytona Coupe is still the only American car to beat Ferrari for a world GT title. The second was that this Superformance continuation car was refined by its original designer, Peter Brock.

Most classic-car enthusiasts know about Peter, but for those who don’t, he grew up wanting to be a racer and car designer. He attended the LA Art Center, studying automotive design for two years until he ran out of money and had to get a job.

Peter landed at General Motors. At age 19, he was one of their youngest-ever designers. Under Bill Mitchell, Peter helped design the 1958 XP87, also known as the Stingray Racer concept car, which eventually morphed into the 1963 Corvette Stingray.

Still, Peter’s dream was to be a racecar driver. In 1961, he left GM to become Carroll Shelby’s first paid employee, hired to run both the Shelby driving school and Shelby’s Goodyear racing tire distributorship for the 11 western states. Peter thought this would be a great way to get his foot in the door and show Carroll what he could do behind the wheel of a car. As the Cobra began to obliterate the Corvettes and other competitors on U.S. circuits, Carroll turned his sights to Enzo Ferrari and European tracks.

One of the hurdles Carroll faced was Europe’s longer tracks. The Cobra was not as aerodynamic as the Ferraris and therefore about 20 mph slower on the three-mile-long Mulsanne Straight at Le Mans, where Ferraris were running 180 mph. Peter told Carroll that he could design a more aerodynamic body that would be faster than Ferrari. The backstory in Peter’s own words:

“My suggestion to build the coupe was based on the aero studies done in Germany in the late ’30s. Because of World War II, no one over here had ever seen anything that looked like what the Germans had figured out. This ‘Kammptailed’ shape was far better than the long-existing belief that a ‘raindrop’ shape with a long tail was the most efficient shape for an automobile. Since no one had ever seen such an ‘ugly shape’ on an automobile, almost everybody in Shelby American was against my concept…. including Phil Remington, who I had the utmost respect for and was hoping he’d back the project. When he told Carroll he wouldn’t work on this stupid idea, Carroll was really undecided on whether to continue. Only Ken Miles, who had almost as much stature within Shelby as ‘Rem,’ believed in the project because he was from England and had seen what the Germans were doing prior to World War II. Ford also refused to back the idea, as they had their own project, the Eric Broadley Lola MK 6, which they had bought to redesign into the Ford GT.

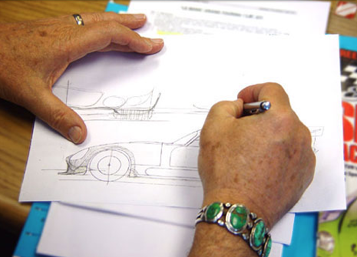

“So with no money, Carroll had nothing… no options! It cost almost nothing to draw up the design. With a couple of quick sketches I’d done, he went to Goodyear and they put up the money. With still-continuing opposition from Remington, almost everyone in the shop refused to work on the project. So, Ken, myself, and John Ohlsen built the buck on which the first panels were formed. Once those were back in the shop, a couple of the good guys, including Donn Allen and Jack Lane, offered to help. Even when we went to Riverside to test there was still little interest, as they knew it would fail. Ken broke the Cobra roadster’s lap record by 3.5 seconds and pushed the speed up to 180… this on a standard Cobra race chassis as required by FIA rules. That test changed everything.

“You know the story at Daytona… lap record and fire, so it wasn’t until Sebring, where MacDonald and Holbert won, that Ford finally agreed to back us for Europe. (The GT40 was way behind schedule.) CSX 2299, the second Daytona, had its body built in Modena and won Le Mans, which put us in the lead for FIA points.”

The rest of the story is that the Daytona won the GT class at Le Mans its first year out in 1964 (despite an oil-cooler failure while leading the overall race) and became the only American car to ever beat Ferrari for a world GT title, in 1965. While at Shelby American, Peter also designed the now-famous Cobra logo, Cobra stripes, and other design elements and liveries of the cars.

Peter went on to build his own race team after the Shelby days, Brock Racing Enterprises (BRE). BRE became the West Coast Datsun factory race team and competed in 1969 in the SCCA DP class with Datsun 2000 roadsters, in 1970 and 1971 in the CP class with the 240Zs (SCCA National Champions 1970-1971), and with the 2.5 Trans-Am Series races in Datsun 510s (National Champions 1971-1972).

Peter’s design skills were not limited to the racetrack. In the early 1970s, Peter founded Ultralite Products, which he built into the largest hang-gliding company in the world. He even developed the sport of competitive long-distance hang-gliding.

Peter is also a photographer, author, and a true Renaissance man. One of his latest projects is the Aerovault car hauler, manufactured alongside Brock Racing Enterprises in Henderson, Nevada. In addition to that, Peter designed a recently launched, limited-edition Baume et Mercier Shelby Daytona Coupe watch.

Circling back to Shelbys, Superformance decided to manufacture and sell a continuation version of the Cobra Daytona Coupe to complement their existing line of 289 and 427 Cobra replicas and continuation cars. Superformance hired Peter Brock and Bob Negstad (chassis designer of the original GT40 program) to refine the original design, providing even more original Shelby DNA. Peter and Bob got to revisit the car without their 1964 limitations of starting with the existing 289 Cobra chassis and a 90-day design deadline. Once Superformance completed a licensing deal with Shelby American, the Daytonas began receiving the prestigious CSX9000 series chassis numbers as well as many upgrades above and beyond the first-generation cars, some of which were more innovations from Peter Brock.

Superformance has now produced almost 200 Shelby CSX9000 series continuation Daytona Coupes. The cars are shipped from the factory as complete “rollers.” (Customers worldwide get to choose their own engine and transmission to complete the cars.)

The chassis design is a work of art in its own right. In a Road & Track test in March 2006, the Daytona recorded a skidpad lateral acceleration of 1.07g and a slalom course speed of 76.6 mph – modern supercar territory. With a small-block Ford pushrod engine (a 351 Windsor stroker motor is the most popular choice), a Daytona Coupe can easily make over 500 HP in a very streetable car capable of 0-60 mph times in the 3.5-second range. Power windows and air conditioning are standard equipment. You can literally drive the car cross country, and then go do a track day and impress (and possibly embarrass) people driving much more modern and expensive cars.